[Disclaimer: I’m not claiming to be an expert on this, please do not use this as an ultimate source of information—do get in touch if any of what I’ve said here is inaccurate.]

Introduction

Students across the country will receive A-Level and BTEC results today. Under normal circumstances, these would be stressful times, but with coronavirus I can only imagine how challenging this must be. These students have not had the opportunity to sit formal exams and demonstrate their skills; nor will they, today, have access to the support and advice their teachers could provide in this challenging process.

The lack of formal exams means that generating accurate and meaningful grades for students is incredibly difficult. From the moment the government cancelled this year’s exams, students, teachers, examination boards, and OFQUAL have all been proposing strategies for this.

Simple Solutions to Difficult Problems

The seemingly obvious strategy would have been to use AS grades. However, since 2017, the government have been phasing out AS levels, under the premise that terminal examinations (those sat at the end of two years) are a better measure of a student’s academic ability. This cohort is the second year-group to have not completed AS Level exams. Similarly, for most subjects, less than 20% of their course is assessed through coursework. Various courses do not have any assessed coursework. So, the idea of using coursework to determine grades is also out of the question.

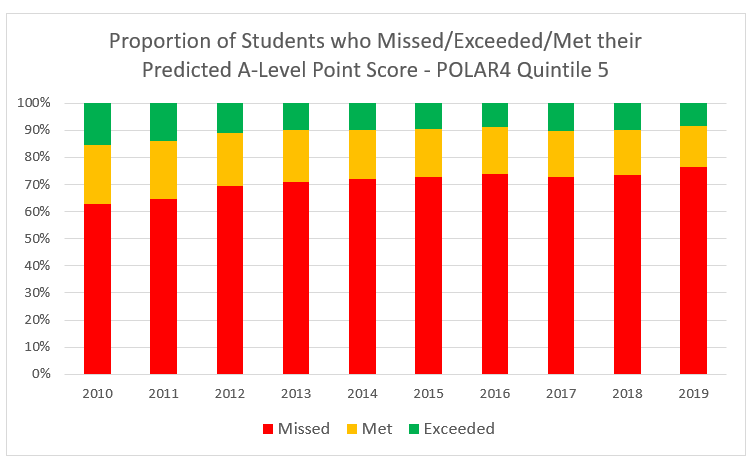

Another seemingly sensible strategy is to use “centre assessed” or “predicted” grades. Unfortunately, predicted grades are atrocious. Some schools put in place rigorous processes to accurately determine predicted grades: well-conducted mock exams and analysis of students expected progress. However, others simply predict the grades a student needs for their university choices. UCAS provides data on the disparity between predicted and achieved grades. The graph below does show that, in many cases, schools (likely unintentionally) inflate predicted grades.

It would not only be statistically inaccurate to award all students their predicted grades, it would be a disservice to the year group themselves.

First, let’s consider the approximately half of students who go on to university. Higher tier universities make more offers than they have places. Cambridge made 4,694 offers and only had 3,528 freshers in 2019; very similar statistics are seen in other years and other universities. By the nature of them being “higher tier”, they are likely to be a student’s “firm choice”. If all students received their “inflated” predicted grades, these universities wouldn’t have the ability to admit this higher number of students.

Now, let’s consider the other half of students that go straight into the world of work. An inflated set of A-Level grades would, counterintuitively, disadvantage this group since employers will see their grades as less accurate and will take them less seriously in this increasingly competitive job market.

So overall, we can see that predicted grades aren’t a suitable solution to the problem. Mock examination results also suffer from the same lack of accuracy and consistency and would not be a suitable solution.

Complex Solutions and Bad Communication

We’ve concluded that students need to receive grades which are roughly in line with previous years. There is not a way to calculate these grades perfectly. If there was, the exam boards would not need to make students sit exams. So, we must resort to some form of “statistical aggregation”. The general strategy set out by all 4 nations to achieve this was as follows:

- Generate a “pot of grades” that the school or sixth form college is likely to have received.

- Get a ranking of students per subject from schools.

- Allocate the “pot of grades” to the students.

Each nation carried this out in a slightly different way. For example, Wales was able to more accurately tailor the “pot of grades” to the specific cohort, since they have nationwide KS3 (year 9) exams. One thing to note is that this system does not explicitly rely on a teacher’s “centre assessed grade”—something which as caused anger among schools and students.

There are several issues with this system. Most obviously, a school’s “pot of grades” is not constant over time. This system is unable to consider the possibility of an outlier year group.

The most prominent issue of this system is the downgrading of “centre assessed grades”. The anger around this is understandable: “my teacher thought I should get an A, why have I only got a C?” This issue becomes more significant when we look at how this has affected different areas.

The graphs below show the difference between predicted and achieved grades in POLAR4 quintiles 1 and 5. POLAR4 is a measure of university progression in an area.

In 2019, 24% of students in quintile 5 areas (with the highest university progression) met or achieved their predicted grades. In the same year, just 15% of students did so in quintile 1 areas. This disparity is also present in most other years. It’s also likely unintentional—most teachers aren’t intentionally inflating grades. What this disparity has inadvertently led to is students’ predications being “downgraded” more in these less advantaged areas, leading to widespread anger and protests in Scotland. The word “downgrade” is slightly misleading in the context of the above methodology.

There are exceptional cases, such as in schools with a small number of students. It would be impossible to generate the “pot of grades” for these small class sizes, and therefore “centre assessed grades” were used here. These circumstances are more likely to occur in private schools and have furthered the above disparity.

The communication of this methodology has been undeniably bad throughout. Many students feel that their grade has been “moderated down” since their “school is bad”.

In response to the widespread criticism, the various government have introduced changes to the system. Including a triple lock where no student will receive a lower grade than their mock exams, and all students have the option to resit exams in October. This system suffers from the same problems described before.

Recently, the following image has circulated on Twitter:

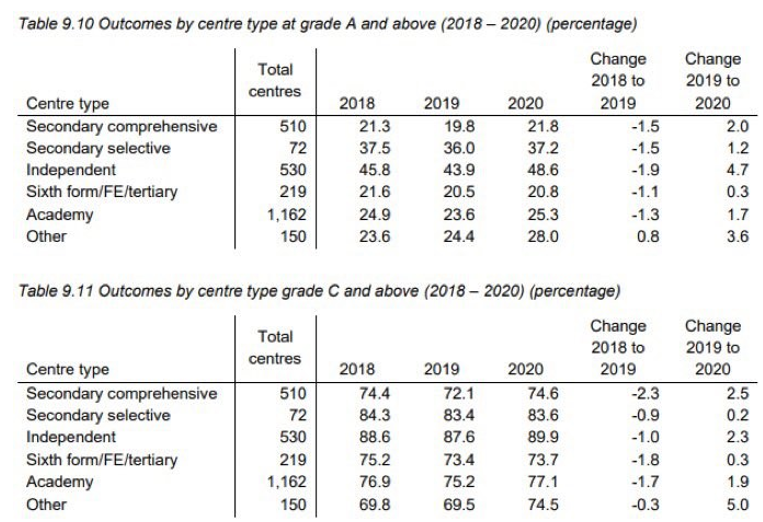

The noticeably lower 2019 results are one cause of the “boost” this year. However, this “grade inflation” that is still occurring is benefiting independent schools more than state schools, especially towards the top end. A possible cause of this is the “small class problem”. Another is structural problems with the calculation methodology described earlier.

Conclusions

Overall, we can see that there is no right way to calculate these results. We’ve now seen another of the many problems with an exam-oriented qualification system that puts more focus on the final grade than the skills developed. For the future, we need to learn from this and set up an education system that works to eliminate these problems and moves away from the concept of “predicted grades”. We must work towards a liberal education system that works for all.

0 Comments